-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kornelia Kotseva, David Wood, Dirk De Bacquer, Guy De Backer, Lars Rydén, Catriona Jennings, Viveca Gyberg, Philippe Amouyel, Jan Bruthans, Almudena Castro Conde, Renata Cífková, Jaap W Deckers, Johan De Sutter, Mirza Dilic, Maryna Dolzhenko, Andrejs Erglis, Zlatko Fras, Dan Gaita, Nina Gotcheva, John Goudevenos, Peter Heuschmann, Aleksandras Laucevicius, Seppo Lehto, Dragan Lovic, Davor Miličić, David Moore, Evagoras Nicolaides, Raphael Oganov, Andrzej Pajak, Nana Pogosova, Zeljko Reiner, Martin Stagmo, Stefan Störk, Lale Tokgözoğlu, Dusko Vulic, the EUROASPIRE Investigators, EUROASPIRE IV: A European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 23, Issue 6, 1 April 2016, Pages 636–648, https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487315569401

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To determine whether the Joint European Societies guidelines on cardiovascular prevention are being followed in everyday clinical practice of secondary prevention and to describe the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients across Europe.

EUROASPIRE IV was a cross-sectional study undertaken at 78 centres from 24 European countries. Patients <80 years with coronary disease who had coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous coronary intervention or an acute coronary syndrome were identified from hospital records and interviewed and examined ≥ 6 months later. A total of 16,426 medical records were reviewed and 7998 patients (24.4% females) interviewed. At interview, 16.0% of patients smoked cigarettes, and 48.6% of those smoking at the time of the event were persistent smokers. Little or no physical activity was reported by 59.9%; 37.6% were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and 58.2% centrally obese (waist circumference ≥ 102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women); 42.7% had blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg (≥140/80 in people with diabetes); 80.5% had low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥ 1.8 mmol/l and 26.8% reported having diabetes. Cardioprotective medication was: anti-platelets 93.8%; beta-blockers 82.6%; angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers 75.1%; and statins 85.7%. Of the patients 50.7% were advised to participate in a cardiac rehabilitation programme and 81.3% of those advised attended at least one-half of the sessions.

A large majority of coronary patients do not achieve the guideline standards for secondary prevention with high prevalences of persistent smoking, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity and consequently most patients are overweight or obese with a high prevalence of diabetes. Risk factor control is inadequate despite high reported use of medications and there are large variations in secondary prevention practice between centres. Less than one-half of the coronary patients access cardiac prevention and rehabilitation programmes. All coronary and vascular patients require a modern preventive cardiology programme, appropriately adapted to medical and cultural settings in each country, to achieve healthier lifestyles, better risk factor control and adherence with cardioprotective medications.

Introduction

The main objectives of cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention are to reduce morbidity and mortality, improve quality of life and increase longevity in good health.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has promoted CVD prevention in clinical practice since 1994.1–5 The aim of the Joint European Societies (JES) guidelines on CVD prevention is to improve the practice of preventive cardiology through development of national guidelines, implementation and evaluation. Patients with coronary or other atherosclerotic disease are the highest clinical priority for prevention with defined goals for lifestyle, medical risk factor management and the use of cardiovascular protective medication.

The EUROASPIRE (European Action on Secondary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events) cross sectional surveys, starting in 1995–1996, have evaluated guideline implementation. Time trends across three surveys have shown adverse lifestyle trends in coronary patients, a substantial increase in obesity and the highest prevalence of persistent smoking in younger patients.6–10 Despite a substantial increase in antihypertensive drug use, blood pressure management remained unchanged over this period with almost one-half of all patients still above the blood pressure target. The largest proportionate increase in prescribing was lipid-lowering drugs, principally statins, with a corresponding improvement in lipid control although most patients were still not below the low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol target. Nearly one-third of patients in EUROASPIRE III had a history of diabetes mellitus with poor glucose control.

The Euro Heart Survey of Diabetes and the Heart, a multicentre prospective observational study in 4961 coronary patients from 25 countries conducted in 2003–2004, demonstrated that abnormal glucose regulation affected a majority of patients with coronary artery disease and routine use of an oral glucose tolerance test is a simple and cost-effective way to improve detection of such metabolic abnormalities.11 Patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes had a much poorer prognosis, which improved considerably with multifactorial evidence based management.12,13 Since then Joint ESC and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) guidelines for management of patients with diabetes, pre-diabetes and CVD have been published.14

The EUROASPIRE IV survey incorporated the Euro Heart Survey on Diabetes to create the first European Survey of CVD Prevention and Diabetes. The assessment of dysglycaemia using an oral glucose tolerance test in all patients with self reported diabetes will be reported elsewhere.

The main objectives of EUROASPIRE IV were to identify risk factors in coronary patients with and without diabetes, describe their management through lifestyle and use of drug therapies and provide an objective assessment of clinical implementation of current scientific knowledge. This article presents the principal results of this fourth survey.

Study population and methods

Geographical area and hospital sampling frame

EUROASPIRE IV was a cross-sectional study carried out in 24 European countries: Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine and the UK. Within each country one or more geographical areas with a defined population were selected and all hospitals serving these populations were identified. A sample of one or more hospitals, or all hospitals, was taken so that any patient presenting within the area with acute symptoms of coronary disease, or requiring revascularization in the form of balloon angioplasty (PCI) or coronary artery surgery (CABG), had an approximately equal chance of being included. Patients admitted to a hospital outside this geographical area were not included in the sample.

Consecutive patients, men and women (≥18 years and <80 years of age at the time of their index event or procedure), with the following first or recurrent clinical diagnoses or treatments for coronary heart disease (CHD) were retrospectively identified from diagnostic registers, hospital discharge lists or other sources: (i) elective or emergency CABG, (ii) elective or emergency PCI, (iii) acute myocardial infarction (AMI; ICD-10 I21), and (iv) acute myocardial ischaemia (ICD-10 I20). The starting date for identification was ≥ 6 months and < 3 years prior to the expected date of the study interview. In each country, the objective was to identify a sufficient number of coronary patients in order to obtain prospective interview data on 400 living patients.

Data collection

Centrally trained research staff undertook data collection. They reviewed patient medical records and interviewed and examined the patients at hospital or home ≥ 6 months after their index coronary event or procedure, using standardized methods and the same instruments in all centres. Information on personal and demographic details, smoking status, history of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, glucose metabolism and medication was obtained from medical records. Self reported information on lifestyle, other risk factor management and medication was obtained at interview. The case record form was translated into all national languages and the self reported questionnaires were all validated versions for each country. All equipment was calibrated according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The following measurements were performed:

Height and weight in light indoor clothes without shoes (SECA scales 701 and measuring stick model 220). Overweight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Waist circumference was measured using a metal tape applied horizontally at the point midway in the mid-axillary line between the lowest rim of the rib cage and the tip of the hip bone (superior iliac crest) with the patient standing.15 Abdominal overweight was defined as a waist circumference of ≥ 80 cm for women and ≥ 94 cm for men and central obesity as a waist circumference of ≥ 88 cm for women and ≥ 102 cm for men.

Blood pressure was measured twice on the right upper arm in a sitting position using an automatic digital sphygmomanometers (Omron M6) and the mean was used for all analyses. Raised blood pressure was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 80 mmHg (JES 4 guidelines) and ≥140/90 mmHg (≥140/80 mmHg in patients with diabetes mellitus; JES5 guidelines).

Breath carbon monoxide was measured in ppm using a smokerlyser (Bedfont Scientific, Model Micro +). Smoking at the time of interview was defined as self-reported smoking, and/or a breath carbon monoxide exceeding 10 ppm.16 Persistent smoking was defined as smoking at interview among patients reporting to be smokers in the month prior to the index event.

Venous (fasting) blood was drawn for serum total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) calculated according to Friedewald's formula.17 Elevated LDL-C concentration was defined as ≥2.5 mmol/l and ≥2.0 mmol/l, if feasible (JES4 guidelines) and as ≥ 1.8 mmol/l (JES5 guidelines). Elevated fasting glucose among patients with diabetes was defined as ≥6.0 mmol/l and elevated HbA1c as ≥ 6.5% (JES4 guidelines) and ≥7.0% (JES5 guidelines).

Habitual physical activity was assessed with the following question: Which of the following four best describes your level of activity outside work? (i) no physical activity weekly; (ii) only light physical activity in most weeks; (iii) vigorous physical activity at least 20 minutes once or twice a week; (iv) vigorous physical activity for at least 20 minutes three or more times a week. The physical activity target was defined as vigorous physical activity for at least 20 minutes once or more times a week.

The laboratory takes part in the Lipid Standardization Program organized by CDC, Atlanta, Georgia, USA and External Quality Assessment Schemes organized by Labquality, Helsinki, Finland. During the course of the study (two months in 2013) the coefficient of variation (mean ± SD) and systematic error (bias) (mean ± SD) were 1.3%±0.2 and 1.7%±1.1 for total cholesterol, 1.6%±0.5 and −1.5%±1.6 for HDL cholesterol, 2.3%±0.1 and −1.2%±2.6 for triglycerides, and 1.9%±0.1 and 1.4%±0.2 for HbA1c, respectively.

Data management

Data management was undertaken by the EURObservational Research Programme at the European Heart House, Nice, France. All data were collected electronically through web based data entry using a unique identification number for country, centre and individual. The data were submitted via the Internet to the data management centre where checks for completeness, internal consistency and accuracy were run. All data were stored under the provisions of the National Data Protection Regulations.

Statistical analyses

Sample size calculations indicated that a sample of 400 patients attending interview was sufficient to estimate prevalences of risk factors with precision of at least 5% and with a confidence interval of 95%. Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the prevalences of risk factors and medication use by country, gender and age at interview. Patients attending interview were compared with patients not interviewed based on information from the discharge letters using Fisher's exact test for proportions. Geographical variation in prevalences was quantified using the median odds ratio (MOR) with 95% confidence intervals, both estimated from a hierarchical model accounting for clustering of patients within countries. The MOR can be interpreted as the median of the theoretical distribution expressing prevalence odds ratios between all possible pairs of centres. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS statistical software (release 9.3) in the Department of Public Health, Ghent University, Belgium.

Ethical procedures

National Co-ordinators were responsible for obtaining Local Research Ethics Committees approvals. Written, informed consent was obtained from each participant by the investigator by a signed declaration. The research assistants signed the Case Record Form to confirm that informed consent was obtained and stored the original signed declaration consent in the patient file.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures were the proportions of coronary patients achieving the lifestyle, risk factors and therapeutic targets as defined in the JES guidelines on CVD prevention (2007 and 2012).

Results

The survey was undertaken at 78 centres in 24 European countries. A total of 16,426 medical records were reviewed and 7998 coronary patients interviewed (interview rate 48.7%).

The median time (interquartile range) between index event and interview was 1.35 years (0.95–1.93 years), ranging from 0.82 years to 2.25 years. A description of the study population enrolled from medical records and numbers of patient interviewed by country, gender and age at index event is presented in the Supplementary Material Table 1 online.

Overall, risk factor recording at discharge was incomplete with large variations between countries. Smoking status and obesity were recorded in 74.0% and 61.9% of the patients, respectively, and in one-fifth of them there was no information recorded on blood pressure (12.8%), lipids (19.4%) or glucose metabolism (19.7%) in the discharge documents. In those with recorded information, the prevalence of smoking was 29.6%, obesity 32.6%, hypertension 77.8%, dyslipidaemia 72.8% and diabetes 30.7%.

Patient interviews and examinations were conducted on 7998 coronary patients (24.4% women). The median time (interquartile range) between the index event and interview was 1.4 years (0.9–1.9 years), ranging from 0.8 years in Turkey to 2.2 years in Spain. The mean (SD) age at interview was 64.0 (9.6) ranging from 58.7 (10.1) years in Turkey to 67.4 (8.9) years in Germany. The most common reasons for not being interviewed were: no response to the invitation letter (34.9%), refused to attend for personal or other reasons (30.3%), patient died (10.4%), no time (8.9%), change in health status (5.4%) and living outside the catchment area (2.7%). Characteristics of interviewed patients by age, gender and information on CVD risk factors and medication from discharge letters are presented in Table 1. Interview participation was significantly lower in women, in smokers and those with abnormal glucose metabolism. Overall, patients with hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and on cardioprotective medication were more willing to participate while smokers were less likely to attend.

Characteristics of interviewed patients by age, sex and information on cardiovascular disease risk factors and medication from discharge letters.a

| . | Interview . | Significance . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No N = 4357 . | Yes N = 7998 . | ||

| Age at index event, mean (SD) | 62.1 (10.5) | 62.5 (9.6) | p = 0.26 |

| Women, % | 28.5 | 24.4 | p < 0.0001 |

| Information from discharge letter | |||

| Smoking, % | 37.7 | 26.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Obesity, % | 31.7 | 33.8 | p = 0.07 |

| Hypertension, % | 75.4 | 78.6 | p = 0.0002 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 72.1 | 74.2 | p = 0.02 |

| Abnormal glucose metabolism, % | 34.2 | 28.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Aspirin/antiplatelets, % | 96.4 | 98.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 82.1 | 86.3 | p < 0.0001 |

| ACE inhibitors, % | 60.2 | 64.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| AT II receptor blockers, % | 10.7 | 12.0 | p = 0.04 |

| Diuretics, % | 29.7 | 29.7 | p = 0.99 |

| Statins, % | 87.5 | 90.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| . | Interview . | Significance . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No N = 4357 . | Yes N = 7998 . | ||

| Age at index event, mean (SD) | 62.1 (10.5) | 62.5 (9.6) | p = 0.26 |

| Women, % | 28.5 | 24.4 | p < 0.0001 |

| Information from discharge letter | |||

| Smoking, % | 37.7 | 26.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Obesity, % | 31.7 | 33.8 | p = 0.07 |

| Hypertension, % | 75.4 | 78.6 | p = 0.0002 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 72.1 | 74.2 | p = 0.02 |

| Abnormal glucose metabolism, % | 34.2 | 28.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Aspirin/antiplatelets, % | 96.4 | 98.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 82.1 | 86.3 | p < 0.0001 |

| ACE inhibitors, % | 60.2 | 64.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| AT II receptor blockers, % | 10.7 | 12.0 | p = 0.04 |

| Diuretics, % | 29.7 | 29.7 | p = 0.99 |

| Statins, % | 87.5 | 90.0 | p < 0.0001 |

aExcluding patients that have died or moved.

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; AT II: angiotensin II

Characteristics of interviewed patients by age, sex and information on cardiovascular disease risk factors and medication from discharge letters.a

| . | Interview . | Significance . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No N = 4357 . | Yes N = 7998 . | ||

| Age at index event, mean (SD) | 62.1 (10.5) | 62.5 (9.6) | p = 0.26 |

| Women, % | 28.5 | 24.4 | p < 0.0001 |

| Information from discharge letter | |||

| Smoking, % | 37.7 | 26.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Obesity, % | 31.7 | 33.8 | p = 0.07 |

| Hypertension, % | 75.4 | 78.6 | p = 0.0002 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 72.1 | 74.2 | p = 0.02 |

| Abnormal glucose metabolism, % | 34.2 | 28.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Aspirin/antiplatelets, % | 96.4 | 98.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 82.1 | 86.3 | p < 0.0001 |

| ACE inhibitors, % | 60.2 | 64.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| AT II receptor blockers, % | 10.7 | 12.0 | p = 0.04 |

| Diuretics, % | 29.7 | 29.7 | p = 0.99 |

| Statins, % | 87.5 | 90.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| . | Interview . | Significance . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No N = 4357 . | Yes N = 7998 . | ||

| Age at index event, mean (SD) | 62.1 (10.5) | 62.5 (9.6) | p = 0.26 |

| Women, % | 28.5 | 24.4 | p < 0.0001 |

| Information from discharge letter | |||

| Smoking, % | 37.7 | 26.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Obesity, % | 31.7 | 33.8 | p = 0.07 |

| Hypertension, % | 75.4 | 78.6 | p = 0.0002 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 72.1 | 74.2 | p = 0.02 |

| Abnormal glucose metabolism, % | 34.2 | 28.2 | p < 0.0001 |

| Aspirin/antiplatelets, % | 96.4 | 98.0 | p < 0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 82.1 | 86.3 | p < 0.0001 |

| ACE inhibitors, % | 60.2 | 64.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| AT II receptor blockers, % | 10.7 | 12.0 | p = 0.04 |

| Diuretics, % | 29.7 | 29.7 | p = 0.99 |

| Statins, % | 87.5 | 90.0 | p < 0.0001 |

aExcluding patients that have died or moved.

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; AT II: angiotensin II

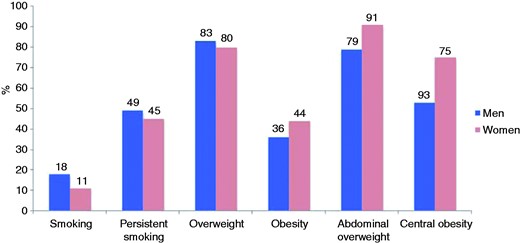

The prevalences of smoking, overweight and obesity in coronary patients are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2 online. The overall prevalence of smoking (self-reported and/or CO in breath > 10 ppm) at interview was 16.0% and highest in patients <50 years (33.6%). The prevalence of persistent smoking among those who were smoking in the month prior to the coronary event was 49.3% and about one-half (50.9%) reported an intention to quit smoking within the next six months. The majority of smokers had received verbal (88.5%) or written (42.6%) advice to stop smoking, but only a small minority (18.6%) was advised to attend a smoking cessation clinic or use pharmacological support in the form of nicotine- replacement therapy (NRT; 22.9%), varenicline (6.2%) or bupropion (4.7%). Two-thirds of persistent smokers (66.7%) reported reducing the amount of smoking after their cardiac event and 7.2% attended a smoking cessation clinic. NRT, bupropion and varenicline were prescribed to 14.4%, 1.7% and 3.1% of these patients, while 28.0% of the persistent smokers reported taking no action to stop smoking since their coronary event.

Prevalence (%) of smoking, persistent smoking, overweight, obesity, abdominal overweight and central obesity by sex at interview.

Smoking: self-reported smoking or > 10 ppm carbon monoxide in breath; persistent smoking: self-reported smoking or > 10 ppm carbon monoxide in breath in patients reporting to have been smoking in the month prior to the index event; overweight: body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2; obesity: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; abdominal overweight: waist circumference ≥ 80 cm for women and ≥ 94 cm for men; central obesity: waist circumference ≥ 88 cm for women and ≥ 102 cm for men.

Nearly nine out of 10 coronary patients were aware of their weight (93.4%) and blood pressure (86.7%). However, less than one-half of them knew their total cholesterol (48.9%), fasting glucose (49.6%) and waist circumference (29.3%). A majority of patients had tried to change their diet since their coronary event by reducing the intake of salt (71.8%), fat (78.9%), sugar (66.1%), alcohol (53.5%) and calories (63.3%), as well as changing fat composition (71.1%) and increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables (77.8%) and fish (66.8%).

The majority of coronary patients increased their physical activity by following specific advice from a health or exercise professional (23.5%), attending a fitness club or leisure centre or joining a community walking group (52.8%), or simply increasing everyday physical activity (17.4%). However, only 40.1% of them (men 43.0%; women 30.8%) reported vigorous physical activity for at least 20 min once or more times a week to increase their physical fitness.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in coronary patients was 82.1% and 37.6%, respectively. A total of 82.0% had abdominal overweight and 58.2% central obesity. Less than one-half (48.1%) of obese patients had followed dietary recommendations since their coronary event, 48.4% increased their regular physical activity levels to lose weight and 3.0% used appetite suppressants or other anti-obesity medications. Nearly one in five of obese patients reported never being told they were overweight. Only one-half of them (49.8%) tried to lose weight within the month prior to the interview and less than two-thirds (61.9%) reported considering losing weight within the next six months.

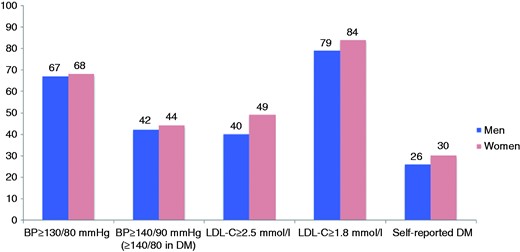

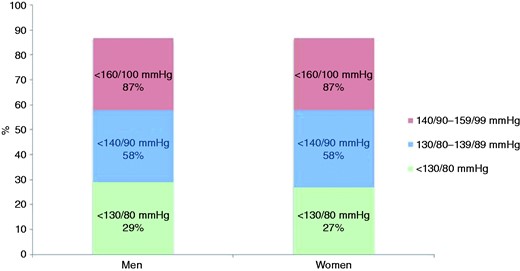

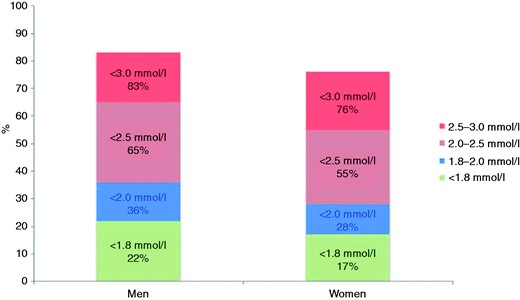

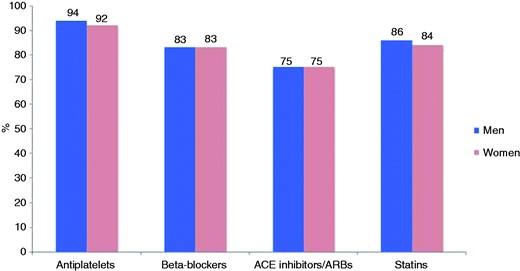

The prevalences of elevated blood pressure, LDL cholesterol and diabetes are presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2 online. Figures 3–5 and Supplementary Table 3 online show the therapeutic control of blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol and diabetes. The reported medication at interview is presented in Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 4 online. Overall, 78.1% of coronary patients were on blood pressure lowering and 86.6% on lipid lowering medications, mainly statins (85.7%). More than nine out of 10 patients were on antiplatelet medication, four-fifths on beta-blockers and three-quarters on angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

Prevalence (%) of elevated blood pressure (BP), raised low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and self-reported diabetes mellitus (DM) by sex at interview.

Proportions (%) at blood pressure target (<130/80 mmHg, < 140/90 mmHg, < 160/100 mmHg) in patients on blood pressure lowering medication) by sex at interview.

Proportions (%) at low-density lipoprotein cholesterol target (<1.8 mmol/l, < 2.0 mmol/l, < 2.5 mmol/l, < 3.0 mmol/l) in patients on lipid lowering medication by sex at interview.

Glycaemic control (HbA1c, %) in people with history of diabetes (glycaemic control: HbA1c < 6.1%, < 6.5%, < 7.0%, < 8.0%, < 9.0%).

Reported cardioprotective medication (%) by sex at interview.

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker

Of the coronary patients 50.7% were advised to participate in a cardiac prevention and rehabilitation programme and 81.3% of those advised attended at least one-half of the sessions. At the time of interview (one or more health professionals could be indicated) 73.0% were under the care of a cardiologist, 62.1% a general practitioner, 10.1% a diabetologist/endocrinologist, 4.5% a specialist cardiac nurse, 4.3% other professional and 5.5% reported no specialist care for their cardiac disease.

Discussion

Although there is compelling scientific evidence for prevention and rehabilitation following the development of coronary disease EUROASPIRE IV reveals a large majority of coronary patients in Europe failing to achieve the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic targets set by the JES guidelines.4,5 There is a large variation between European countries both in lifestyle and risk factor management, the use of cardioprotective medications, the provision of cardiac prevention and rehabilitation and other preventive services. Information on risk factors and management in discharge documents is incomplete, especially for lifestyles.

There is a wealth of evidence that achieving a healthier lifestyle reduces the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in coronary patients and improves quality of life and longevity. Almost one-half of those who smoked before the event were still smokers at follow-up and the prevalence of smoking among these persistent smokers was highest in younger patients, < 50 years, both men and women. Stopping smoking after a myocardial infarction is a really effective preventive action.18–20 A meta-analysis of smoking cessation after a myocardial infarction showed a relative risk reduction for coronary mortality of 46%18 and a Cochrane meta-analysis reported a 36% reduction in all cause mortality.19 Yet despite this evidence less than one in five of those still smoking were advised to attend a smoking cessation clinic, and only a small minority did so. Pharmacotherapies to support smoking cessation were not widely used. All cigarette smokers with vascular disease should be professionally supported to stop smoking. In a randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led behavioural smoking intervention in high risk persistent smokers, supplemented with optional varenicline, 51% of vascular patients had stopped smoking at 16 weeks.20 A specialist smoking cessation clinic for patients with CVD achieved abstinence in one-third using varenicline, and this was associated with significant reductions in re-hospitalization and all cause mortality after two years.21

A majority of coronary patients in EUROASPIRE IV reported increasing physical activity levels and changing diet since hospitalization. However, only four out of 10 achieved a physical activity level of vigorous intensity for at least 20 minutes one or more times a week. Patients should receive professional advice on healthy eating and how to safely increase their physical activity to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity and overall risk of CVD. In EUROASPIRE IV a majority of coronary patients were overweight or obese, many with central obesity as well, contributing to the highest prevalence of diabetes ever recorded in these surveys. Many obese patients were uninformed about their weight and nearly one-half did not follow any dietary recommendations or increase their physical activity levels. Many had no plans to lose weight.

In EUROASPIRE IV, although information on hypertension was well recorded in discharge documents, less than one-third of coronary patients on blood pressure medication had reached the recommended target at that time of <130/80 mmHg. The 2012 JES guidelines recommended a more conservative target of <140/90 mmHg (<140/80 mmHg in patients with diabetes) based on recent trial evidence,22 but even this was not achieved by more than two-fifths of the patients despite a recent meta-analysis of trial evidence showing that a reduction of SBP by 10 mmHg, or DBP by 5 mmHg, reduces CHD events (fatal and non-fatal) by about one-quarter and stroke by about one-third.23

Statin therapy can safely reduce the five-year incidence of coronary events, revascularization and stroke by about one-fifth per mmol/l of LDL cholesterol reduction, regardless of the starting level.24 Information on dyslipidaemia was recorded in most of the patients' medical notes but at interview less than two-thirds of coronary patients had reached the conservative LDL cholesterol target of <2.5 mmol/l despite lipid-lowering therapy. Patients with a baseline LDL-cholesterol < 2.0 mmol/l will have the same proportionate reduction in CVD risk as those with higher levels25 and therefore the JES 2012 prevention guidelines recommended lowering LDL-cholesterol to ≤ 1.8 mmol/l in patients with established CVD.5 In EUROASPIRE IV only one-fifth of those on lipid-lowering medication achieved this lower target and therefore coronary patients require more intensive cholesterol management.

Self reported diabetes was found in about one-quarter of these coronary patients. Glucose control in previously diagnosed diabetes was poor with just over one-third achieving the JES4 target for HbA1c < 6.5% and still less than half using the new JES5 target HbA1c of < 7.0 mmol/l. The latter target still reduces the risk of microvascular complications, but macrovascular complications to a lesser extent.26–28

Cardioprotective drug therapies are recommended in the JES4 and JES5 guidelines for CVD prevention.4,5 A majority of patients in EUROASPIRE IV reported taking these drug classes. Explanations for inadequate blood pressure and lipid control may include starting with a low dose and not up-titrating, not using a combination of drug therapies with different modes of action for blood pressure, and poor patient adherence. The last is associated with higher cardiovascular event rates, all-cause mortality, and increased health care costs.29,30 A meta-analysis of observational studies demonstrated that good adherence to drug therapy is associated with positive health outcomes.31 Thus, there is further potential to reduce recurrent cardiovascular events through optimizing dosages to those used in trials and promoting adherence to prescriptions.

In order to achieve healthier lifestyles, more effective risk factor management and adherence with medications, patients require comprehensive prevention and rehabilitation programmes. There is compelling scientific evidence that secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation are effective services for patients with CHD. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials show that structured, compared with standard, care is associated with a reduction in all-cause and cardiac mortality.32–34 More recently an observational analysis from the OASIS trial in acute coronary syndrome patients showed that adherence to behavioural advice (diet, exercise and smoking cessation) was associated with a substantially lower risk of recurrent cardiovascular events.35 Quitting smoking decreased the risk of myocardial infarction compared with persistent smoking (odds ratio (OR), 0.57; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.36–0.89), and similarly for diet and exercise adherence (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.4–0.69) compared with non-adherence. However, despite the strength of the trial and observational evidence, cardiac prevention and rehabilitation in Europe continues to be widely underused with enormous heterogeneity in service provision between countries. Overall less than one-half of coronary patients access such services and there are large differences in other preventive practices as well. Regrettably, these results are similar to those of EUROASPIRE III, which showed that only one-third actually attended some form of cardiac prevention and rehabilitation.36 So there is considerable potential to further reduce the risk of recurrent CVD through formal prevention and rehabilitation services. Recent studies, such as EUROACTION and EUROACTION Plus, and GlObal Secondary Prevention strategiEs to Limit (GOSPEL), provide contemporary scientific evidence for a comprehensive and sustained approach to preventive and rehabilitative care in which structured programmes achieve healthier lifestyles and more effective risk factor control compared with usual care.20,37,38 A health economics analysis from EUROASPIRE III showed the benefits of closing the treatment gap for prevention with an average incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of Euro 12,484 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY).39 Therefore, all coronary patients should be offered a structured, multidisciplinary prevention and rehabilitation programme.

The results of EUROASPIRE IV are in accordance with earlier multinational surveys of secondary prevention practice conducted in Europe, United States and other parts of the world.40–44 The results of the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry,40 the World Health Organization study on Prevention of Recurrences of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke (WHO-PREMISE),41 STabilization of Atherosclerotic plaque By Initiation of darapLadIb TherapY (STABILITY) trial42 and the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study43,44 demonstrated high prevalences of under treatment and poor control of cardiovascular risk factors in coronary patients in many regions of the world. These regional differences were more marked for obesity and LDL cholesterol attainment. Findings from the PURE study among 7519 patients with self-reported CVD (CHD or stroke) from 17 high, middle or low-income countries worldwide showed lower use of cardioprotective medications compared with EUROASPIRE IV, with only 25% being on antiplatelet drugs, 17% on beta-blockers, 20% on ACE inhibitors or ARBs and 15% on statins.44

The EUROASPIRE IV survey has several limitations. First, patients were recruited from selected geographical areas and hospitals and results cannot be regarded as representative of countries. In every country at least one cardiac centre providing cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology was selected and many were academic specialist centres. Although this is a source of bias it is likely to be conservative as the standard of care in these academic centres is probably higher, and therefore results for patients seen in everyday clinical practice are likely to be poorer. The average interview rate was low at 48.7%, reflecting falling participation in medical research generally,45 but also restrictions imposed by ethics committees and privacy laws in different countries on the ways in which, and how often, patients can be approached. This also introduces a potential bias but non-participants are more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles and poorer risk factor control and therefore our data are under estimating the true status of preventive cardiology practice across Europe. The main strength of the EUROASPIRE surveys is that data are based on interviews and standardized examinations, including central laboratory analyses, rather than medical records, which are often incomplete for risk factor recording. Therefore, this survey provides high quality comparative information on preventive care.

Conclusions

EUROASPIRE IV continues to show that implementation of evidence based guidelines on secondary prevention is far from optimal with high prevalences of smoking, especially among younger coronary patients, obesity, central obesity and diabetes. Although most patients are receiving cardioprotective drugs, therapeutic targets for risk factors are not being achieved in far too many patients. Less than one-half of all coronary patients benefit from cardiac prevention and rehabilitation.

A new approach to cardiovascular prevention is required which integrates cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention into modern preventive cardiology programmes with appropriate adaptation to medical and cultural settings in each country. Preventive cardiology should involve multidisciplinary teams of health care professionals, focusing on lifestyles of patients and their families, in order to achieve the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic targets for coronary and other vascular patients which will reduce their risk of recurrent CVD events, improve quality of life and survival.

Acknowledgements

The EUROASPIRE IV survey was carried out under the auspices of the European Society of Cardiology, EURObservational Research Programme. The sponsors of the EUROASPIRE surveys had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, decision to publish, or writing the manuscript. The EUROASPIRE Study Group is grateful to the administrative staff, physicians, nurses and other personnel in the hospitals in which the survey was carried out and to all patients who participated in the surveys (See Appendix).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that (1) KK, DDB, CJ, VG, LR and DW had grant support from the European Society of Cardiology for the submitted work; VG was supported by a grant from the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation; AP was supported by a grant from Polish National Science Centre (Contract DEC-2011/03/B/N27/06101); JB was supported by the grant No. NT 13186 by the Internal Grant Agency, Ministry of Health, Czech Republic; DM had grants from Servier, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis, Menarini; PA had grants from AstraZeneca; SS had grants from German Ministry of Research and Education via the Comprehensive Heart Failure Centre, University of Würzburg; (2) DW, LR, KK, VG, PA, MD, MS, PH, RC, AE, DG, ZR, LT had the following financial activities outside the submitted work in the previous three years: DW, honoraria for invited lectures or advisory boards: AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Zentiva; consultancy: Merck Sharp and Dohme; LR, grants from Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Diabetes Association, Roche AG, Bayer AG and Karolinska Institute Funds, personal fees from Roche, SanofiAventis, and Bayer AG; KK, travel grants from Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim; VG, lecture fees from MSD Sweden; PA had grants and personal fees from Fondation Plan Alzheimer, Servier, Alzprotect, Total, Hoffman Roche, Daichi Sankyo, Genoscreen; MD, grants from Universal Agency ‘Profarma’; MS was temporarily employed by MSD Sweden AB as Associate Director, medical affairs, during part of the study period; PH receives/received in the recent years research support from the German Ministry of Research and Education (Centre for Stroke Research Berlin; Comprehensive Heart Failure Centre Würzburg), the European Union (European Implementation Score Collaboration), the German Stroke Foundation, the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Berlin Chamber of Physicians, and the University Hospital of Würzburg; RC had grants from Krka, Novo Mesto, Slovenia, personal fees from Servier International, Medtronic, Medtronic Czechia, Abbott Products Operations AG, MSD Czech Republic, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Czech Republic; ZR had personal fees from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Abbott, and Aegirion; AE had grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, Biotronik, Cordis J&J, Medtronik; DG had personal fees from AstraZaneca, Abbott, Novartis and Sanofi; LT had lecture honoraria from Abbott, MSD, Bayer, AstraZaneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, Kowa and Actelion, and (3) ACC, JWD, JDS, MD, ZF, DL, NG, AL, DL, EN, RO, NP, DV have no financial interests that are relevant to the submitted work.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by AstraZeneca, Bristol–Myers Squibb/Emea Sarl, GlaxoSmithKline, F Hoffman–La Roche (Gold Sponsors), Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Amgen (Bronze Sponsors) (unrestricted research grants to the European Society of Cardiology).

Supplementary material

Supplementary Material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Statement of responsibility

The authors had full access to the data and took responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agreed to the written manuscript.

References

- obesity

- physical activity

- smoking

- ldl cholesterol lipoproteins

- statins

- diabetes mellitus

- diabetes mellitus, type 2

- blood pressure

- cardiovascular system

- life style

- guidelines

- heart

- rehabilitation

- persistence

- secondary prevention

- euroaspire trial

- overweight

- prevention

- european society of cardiology

- smokers

Comments