Abstract

Background

Physical activity is known to relieve the metabolic complications of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and exercise is also associated with telomere biology. We investigated the changes induced by progressive resistance training (PRT) in telomere content and metabolic disorder in women with PCOS and controls.

Participants and Methods

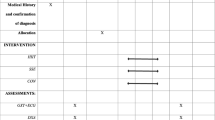

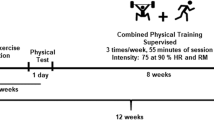

Forty-five women with PCOS and 52 healthy women aged 18 to 37 years were submitted to PRT. A linear periodization of PRT was prepared based on a trend of decreasing volume and intensity throughout the training period. The volunteers performed PRT 3 times a week for 4 months. The participants’ physical characteristics and hormonal concentrations were measured before and after PRT, as telomere content that was measured using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Briefly, Progressive resistance training reduced waist circumference, body fat percentage, plasma testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations, glycemia, and free androgen index. Fasting insulin and insulin resistance index were greater in women with PCOS. Androstenedione and homocysteine increased after PRT. There were no differences in telomere content between controls (0.96 ± 0.3 before vs 0.85 ± 0.21 after) and women with PCOS (0.94 ± 0.33 before vs 0.88 ± 0.39 after). Adjusted analysis showed telomere shortening after PRT in all women (0.95 ± 0.31 before vs 0.86 ± 0.31 after; P = .03). In women with PCOS, increased homocysteine levels were related to telomere reduction and increased androstenedione was positively correlated with telomere content after PRT.

Conclusions

Progressive resistance training had positive effects on the hormonal and physical characteristics of women with PCOS and controls, but telomere content was reduced and homocysteine level increased in all participants.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Balen A, Michelmore K. What is polycystic ovary syndrome? Are national views important? Human Reprod. 2002;17(9): 2219–2227.

March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Phillips DI, Norman RJ, Davies MJ. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(2):544–551.

Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;89(6):2745–2749.

Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010;8:41.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19–25.

Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Vicennati V, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Obesit Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(7):883–896.

Legro RS. Obesity and PCOS: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30(6):496–506.

Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(3):462–477.

Harrison CL, Lombard CB, Moran LJ, Teede HJ. Exercise therapy in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(2):171–183.

Hutchison SK, Stepto NK, Harrison CL, Moran LJ, Strauss BJ, Teede HJ. Effects of exercise on insulin resistance and body composition in overweight and obese women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2011; 96(1):E48–E56.

Park SK, Park JH, Kwon YC, Kim HS, Yoon MS, Park HT. The effect of combined aerobic and resistance exercise training on abdominal fat in obese middle-aged women. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2003;22(3): 129–135.

Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boule NG, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(6): 357–369.

Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(2): 364–380.

Kraemer WJ, Nindl BC, Ratamess NA, et al. Changes in muscle hypertrophy in women with periodized resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):697–708.

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):674–688.

Cheema BS, Vizza L, Swaraj S. Progressive resistance training in polycystic ovary syndrome: can pumping iron improve clinical outcomes? Sports Med. 2014;44(9):1197–1207.

Ludlow AT, Roth SM. Physical activity and telomere biology: exploring the link with aging-related disease prevention. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:790378.

Osthus IB, Sgura A, Berardinelli F, et al. Telomere length and long-term endurance exercise: does exercise training affect biological age? A pilot study. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e52769.

Puterman E, Lin J, Blackburn E, O’Donovan A, Adler N, Epel E. The power of exercise: buffering the effect of chronic stress on telomere length. PloS One. 2010;5(5):e10837.

Tiainen AM, Mannisto S, Blomstedt PA, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and its relation to food and nutrient intake in an elderly population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(12):1290–1294.

Wong JY, De Vivo I, Lin X, Fang SC, Christiani DC. The relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and telomere length in an occupational prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2014; 9(1):e87348.

Butts S, Riethman H, Ratcliffe S, Shaunik A, Coutifaris C, Barnhart K. Correlation of telomere length and telomerase activity with occult ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4835–4843.

Baird DM, Kipling D. The extent and significance of telomere loss with age. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1019:265–268.

Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(24):2353–2365.

Liu JP, Li H. Telomerase in the ovary. Reproduction. 2010; 140(2):215–222.

Agarwal S, Loh YH, McLoughlin EM, et al. Telomere elongation in induced pluripotent stem cells from dyskeratosis congenita patients. Nature. 2010;464(7286):292–296.

Hagelstrom RT, Blagoev KB, Niedernhofer LJ, Goodwin EH, Bailey SM. Hyper telomere recombination accelerates replicative senescence and may promote premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15768–15773.

Lentz SR, Haynes WG. Homocysteine: is it a clinically important cardiovascular risk factor? Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(9): 729–734.

Duleba AJ, Dokras A. Is PCOS an inflammatory process? Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):7–12.

Hulsmans M, Holvoet P. The vicious circle between oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(1–2):70–78.

O’Donovan A, Pantell MS, Puterman E, et al. Cumulative inflammatory load is associated with short leukocyte telomere length in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. PloS One. 2011; 6(5):e19687.

Richards JB, Valdes AM, Gardner JP, et al. Homocysteine levels and leukocyte telomere length. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200(2): 271–277.

Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Inflammatory cytokines induce DNA damage and inhibit DNA repair in cholangiocarcinoma cells by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2000;60(1):184–190.

Pedroso DC, Miranda-Furtado CL, Kogure GS, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and telomere length in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(2):542–547. e542.

Zhang D, Wen X, Wu W, Xu E, Zhang Y, Cui W. Homocysteinerelated hTERT DNA demethylation contributes to shortened leukocyte telomere length in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013; 231(1):173–179.

Calado RT, Yewdell WT, Wilkerson KL, et al. Sex hormones, acting on the TERT gene, increase telomerase activity in human primary hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2009;114(11):2236–2243.

Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sport Sci. 1992;17(4):338–345.

Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(6):981–1030.

American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3): 687–708.

Rhea MR, Ball SD, Phillips WT, Burkett LN. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2002; 16(2): 250–255.

Matuszak ME, Fry AC, Weiss LW, Ireland TR, McKnight MM. Effect of rest interval length on repeated 1 repetition maximum back squats. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(4):634–637.

Calado RT, Brudno J, Mehta P, et al. Constitutional telomerase mutations are genetic risk factors for cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1600–1607.

Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(3):e21.

Scheinberg P, Cooper JN, Sloand EM, Wu CO, Calado RT, Young NS. Association of telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes with hematopoietic relapse, malignant transformation, and survival in severe aplastic anemia. JAMA. 2010;304(12): 1358–1364.

International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment. 1 ed. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. Australia: The University of South Australia; 2001.

Slaughter MH, Lohman TG, Boileau RA, et al. Influence of maturation on relationship of skinfolds to body density: a cross-sectional study. Hum Biol. 1984;56(4):681–689.

Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980; 12(3):175–181.

Siri WE. Body composition from fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. 1961. Nutrition. 1993;9(5):480–491; discussion 480, 492.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000; 894: i-xii, 1–253.

Cascella T, Palomba S, Tauchmanova L, et al. Serum aldosterone concentration and cardiovascular risk in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11): 4395–4400.

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7): 412–419.

Prestes J, Donato FF, Leite RD, Cardoso LC, Stanganelli LCR. Efeitos do treinamento de força periodizado sobre a composição corporal e níveis de força máxima em mulheres. Rev Bras Educ Fisica Esporte Lazer e Dança. 2008;3(3):50–60.

Burr JF, Shephard RJ, Riddell MC. Physical activity in type 1 diabetes mellitus: assessing risks for physical activity clearance and prescription. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(5):533–535.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement: executive summary. Crit Path Cardiol. 2005;4(4): 198–203.

Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults—The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(suppl 2):51S-209S.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162(18):2074–2079.

Enea C, Boisseau N, Fargeas-Gluck MA, Diaz V, Dugue B. Circulating androgens in women: exercise-induced changes. Sports Med. 2011;41(1):1–15.

von Kanel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Regular physical activity moderates cardiometabolic risk in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(1):181–189.

Harrison CL, Stepto NK, Hutchison SK, Teede HJ. The impact of intensified exercise training on insulin resistance and fitness in overweight and obese women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;76(3):351–357.

Nourbakhsh M, Golestani A, Zahrai M, Modarressi MH, Malekpour Z, Karami-Tehrani F. Androgens stimulate telomerase expression, activity and phosphorylation in ovarian adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;330(1–2):10–16.

LaRocca TJ, Seals DR, Pierce GL. Leukocyte telomere length is preserved with aging in endurance exercise-trained adults and related to maximal aerobic capacity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010; 131(2):165–167.

Ludlow AT, Zimmerman JB, Witkowski S, Hearn JW, Hatfield BD, Roth SM. Relationship between physical activity level, telomere length, and telomerase activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40(10):1764–1771.

Zhu H, Wang X, Gutin B, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in healthy Caucasian and African-American adolescents: relationships with race, sex, adiposity, adipokines, and physical activity. J Pediatr. 2011;158(2):215–220.

Collins M, Renault V, Grobler LA, et al. Athletes with exercise-associated fatigue have abnormally short muscle DNA telomeres. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(9):1524–1528.

Werner C, Furster T, Widmann T, et al. Physical exercise prevents cellular senescence in circulating leukocytes and in the vessel wall. Circulation. 2009;120(24):2438–2447.

Calado RT, Cooper JN, Padilla-Nash HM, et al. Short telomeres result in chromosomal instability in hematopoietic cells and precede malignant evolution in human aplastic anemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):700–707.

Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Telomere shortening unrelated to smoking, body weight, physical activity, and alcohol intake: 4,576 general population individuals with repeat measurements 10 years apart. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004191.

Ren H, Zhao T, Wang X, et al. Leptin upregulates telomerase activity and transcription of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394(1):59–63.

McCarthy DA, Perry JD, Melsom RD, Dale MM. Leucocytosis induced by exercise. BMJ. 1987;295(6599):636.

Robertson JD, Gale RE, Wynn RF, et al. Dynamics of telomere shortening in neutrophils and T lymphocytes during ageing and the relationship to skewed X chromosome inactivation patterns. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(2):272–279.

Li Q, Du J, Feng R, et al. A possible new mechanism in the pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the discovery that leukocyte telomere length is strongly associated with PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E234–E240.

Song Z, von Figura G, Liu Y, et al. Lifestyle impacts on the aging-associated expression of biomarkers of DNA damage and telomere dysfunction in human blood. Aging Cell. 2010;9(4): 607–615.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miranda-Furtado, C.L., Ramos, F.K.P., Kogure, G.S. et al. A Nonrandomized Trial of Progressive Resistance Training Intervention in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Implications in Telomere Content. Reprod. Sci. 23, 644–654 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719115611753

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719115611753